Even more than a century after its sinking, the RMS Titanic continues to captivate people around the world. Its maiden voyage ended in one of the greatest peacetime maritime disasters in history. This blog post examines the facts about the luxury liner, discusses speculations and alternative theories, reviews popular conspiracy theories, and looks at latest developments up to 2025 – including recent expeditions and research findings. Finally, key figures provide a quick overview of the Titanic’s technical details and casualty numbers.

Facts and Historical Background

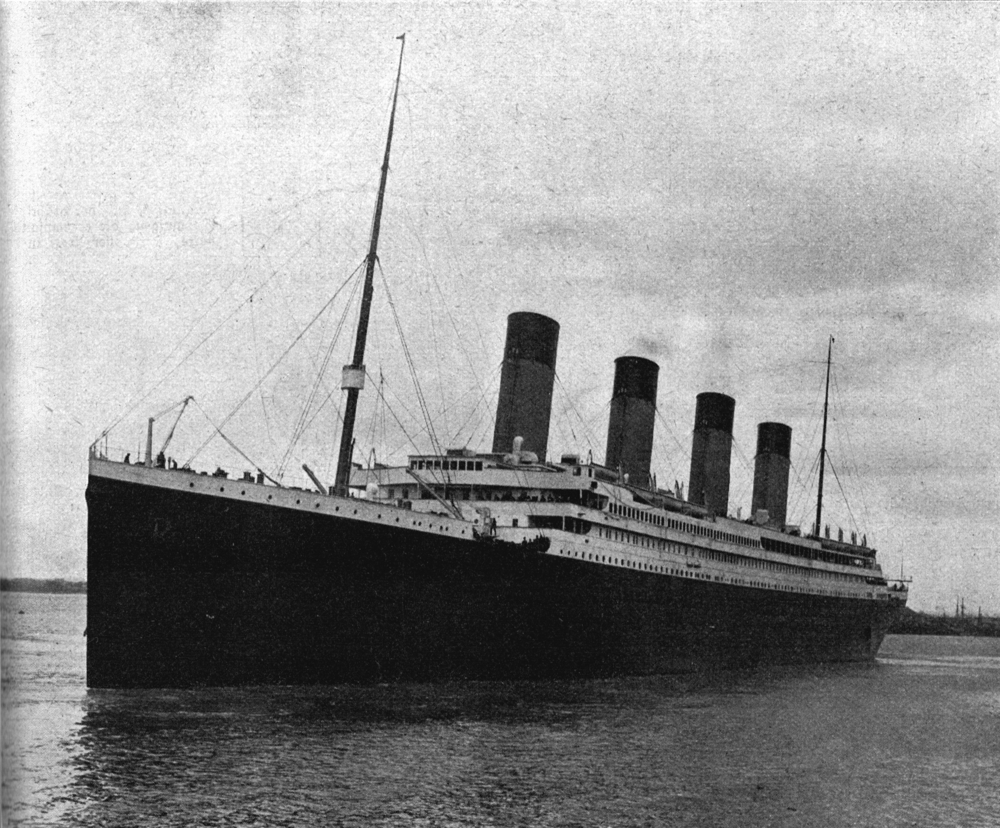

Construction and Features: The Titanic was commissioned by the White Star Line and built by Harland & Wolff in Belfast. It was the second of three planned Olympic-class liners (alongside Olympic and Britannic) and at the time of entering service it was the largest ship in the world. The hull measured 269 m in length with a 28 m beam, had nine decks, and a tonnage of about 46,000 GRT. Driven by three propellers and powerful steam engines delivering around 46,000 HP, it could achieve up to 23 knots of speed. Titanic could accommodate about 2,435 passengers plus some 900 crew, and it epitomized luxury – featuring opulent salons, a swimming pool, and a grand staircase. Contemporary media dubbed the ship “practically unsinkable,” as it was divided into 16 watertight compartments. In theory, the ship could stay afloat with any four of these compartments flooded – a safety feature that was ultimately overcome by the circumstances of the tragedy.

Maiden Voyage: On April 10, 1912, Titanic departed Southampton, England, on her first Atlantic crossing bound for New York. Along the way, she made scheduled stops at Cherbourg, France and Queenstown (now Cobh), Ireland to pick up additional passengers. In total about 2,200 people were on board, including some of the wealthiest individuals of the age (e.g. John Jacob Astor, Benjamin Guggenheim, Isidor Straus) as well as hundreds of emigrants from Europe. Captain Edward J. Smith, an experienced mariner nearing retirement, was in command. Despite several ice warnings, Titanic continued through the clear, cold night of April 14, 1912 at high speed (around 22 knots). At about 11:40 PM, the lookouts spotted an iceberg dead ahead. First Officer William Murdoch attempted to avoid it, ordering “hard-a-starboard” (to turn the ship left) and putting the engines full astern. Seconds later, Titanic’s starboard side grazed the iceberg. The collision punctured the hull below the waterline in several places, and at least five of the watertight compartments began flooding in succession – a fatal number that sealed the ship’s fate.

Sinking and Rescue: On the night of April 14–15, 1912, a dramatic evacuation unfolded aboard Titanic. The ship’s bow dipped noticeably within minutes as water flooded the forward sections. By 12:05 AM, Captain Smith ordered the lifeboats uncovered and passengers mustered. Although 20 lifeboats with capacity for 1,178 people were available, this was only about half of the total passengers and crew. Moreover, many boats launched not fully loaded, as the crew was unsure if the davits could bear the weight of a full boat. Women and children were given priority, leaving many husbands and male passengers behind. At 12:15 AM, the wireless operator sent the distress call CQD, later SOS, but the nearest ship (the SS Californian) did not respond in time. Instead, the RMS Carpathia, about 58 miles away, steamed towards Titanic’s position. By 2:10 AM, Titanic’s stern rose high into the air; the ship broke in two and, at 2:20 AM, the great liner slipped fully beneath the North Atlantic waves. Over 1,500 people perished in the frigid waters.Some 706 survivors managed to cling to life in the lifeboats until around 4:10 AM, when they were rescued by Carpathia. This appalling disaster – the Titanic lost on her maiden voyage – shocked the world and led to sweeping changes in maritime safety regulations. For example, henceforth ships were required to carry enough lifeboats for all on board, and since 1914 an international Ice Patrol has monitored North Atlantic shipping lanes for icebergs.

Speculations and Alternative Theories

Technical Weaknesses: Immediately after the disaster, people debated whether material or design flaws had contributed to the scale of the catastrophe. One hypothesis focused on the quality of the rivets and hull steel. Investigations later found that Titanic had been built with some suboptimal materials: analyses in 1998 showed the ship’s iron rivets contained an unusually high concentration of slag, which made them brittle in cold conditions. These brittle rivets may have snapped en masse upon impact – indeed, sonar scans of the wreck found only narrow separations in the hull, rather than one long gash. Titanic’s steel plates were also described as relatively brittle in icy water, potentially prone to cracking. Additionally, the ship’s watertight bulkheads only extended up to E deck; once water spilled over one compartment, it could flow freely into the next. Critics have noted that a full inner bulkhead deck (a continuous “half deck” acting as a flood barrier) might have slowed the sinking. Despite such speculation, it is unquestioned that the iceberg collision was the primary cause of the sinking – but better materials and design might have kept the ship afloat longer.

Navigation and Decisions: There has also been much speculation about human errors in judgment. Captain Smith was later criticized for not slowing down despite ice warnings. In fact, Titanic maintained her speed even though other ships nearby (such as the Californian) had stopped for the ice field. Some suspect that Smith or White Star management pressed to set a speed record or arrive ahead of schedule – an assertion White Star director J. Bruce Ismay denied in inquiries.Another oft-cited factor is that the lookout team had no binoculars, which may have delayed spotting the iceberg. There’s also debate about the helm maneuver during the collision: Murdoch’s instinctive response (hard turn and reversing engines) was understandable, but some experts have asked whether a head-on impact would have been less catastrophic. Modern analyses suggest that if Titanic had struck the iceberg head-on, the ship likely would have been damaged but might not have sunk. Likewise, it’s discussed whether the ship possibly rode up on a submerged spur of ice (a form of grounding), causing additional hull damage – a theory recently revisited through new wreck data (see Latest Developments). Overall, questions remain as to whether different decisions – such as slower speed, better lookout vigilance, or a different evasive action – might have mitigated the disaster.

Coal Bunker Fire: A more recent theory involves a smoldering coal fire in Titanic’s bunkers. In the days before departure, a fire had reportedly broken out in coal bunker No. 6, where fuel for the boilers was stored.Such coal bunker fires were not uncommon at the time, and on Titanic the crew allegedly continued trying to control the fire even as the voyage began.Proponents of this theory – notably Irish journalist Senan Molony – believe the intense heat of the fire weakened the steel structure of the ship’s hull adjacent to the bunker.In fact, a photograph of Titanic before departure shows a dark smudge on the starboard side of the hull in the area of the boiler rooms. Molony and others interpret this marking as an external sign of the internal fire. The fire theory suggests that the iceberg happened to strike right at that pre-weakened section of the hull, causing a far more disastrous breach. Metallurgists cited in Molony’s documentary estimate that extreme heat could reduce steel’s strength by up to 75%. However, this hypothesis remains controversial. Historians such as David Hill of the British Titanic Society doubt that the coal fire made a significant difference. The fire was indeed mentioned in the official 1912 inquiries, but there is no evidence it structurally compromised the hull in any decisive way. Most experts still regard the collision with the iceberg – combined with excessive speed and an inadequate evacuation – as the primary cause of the sinking.

Conspiracy Theories

The Titanic–Olympic Switch: One of the most popular conspiracy theories about the disaster claims that the ship never truly sank – because it had been secretly swapped. According to this theory, the badly damaged Olympic (Titanic’s nearly identical sister ship) was switched with Titanic in port. White Star Line then supposedly sailed the slightly modified Olympic under the name Titanic to commit insurance fraud: the idea being that the older ship would be deliberately wrecked for an insurance payout, while the real Titanic would quietly continue in service.Proponents point to the financial losses Olympic incurred after a collision in 1911 and speculate that White Star acted out of greed. Historians and experts refute this claim: for one, Titanic’s insurance payout would not have been nearly enough to cover the loss of Olympic.Moreover, there were numerous design differences between Titanic and Olympic – such as the arrangement of windows and serial numbers on parts – that have been clearly identified on the wreck as belonging to Titanic. These documented differences definitively debunk the switch theory. Even so, the idea persists in books, internet forums, and social media to this day, most recently revived by the public interest surrounding a Titanic submersible mission in 2023.

Financial Plot – J. P. Morgan and the “Enemy Millionaires”: Another conspiracy theory asserts that American banker J. P. Morgan orchestrated the sinking of the Titanic to kill off rivals. Morgan, who had large interests in White Star Line, indeed booked a voyage on Titanic but cancelled at the last minute. The theory claims the disaster was meant to eliminate three wealthy tycoons on board: John Jacob Astor, Isidor Straus, and Benjamin Guggenheim – all powerful millionaires who perished in the sinking. This, it’s alleged, benefited Morgan because they supposedly opposed the creation of the U.S. Federal Reserve banking system. Some versions even suggest a conspiracy by the Rothschild banking family or the Jesuit order was behind the sinking. Historians point out that there is no evidence for these claims whatsoever. There is no plausible explanation for how Morgan could have deliberately steered the ship into an iceberg or staged the disaster. Additionally, there’s no indication that Astor or Guggenheim actually opposed the Federal Reserve – in fact, Straus openly supported it. The construction of such a “financial plot” often plays into antisemitic tropes (for example by invoking the Rothschilds) and lacks any historical basis. J. P. Morgan was certainly influential, but there is no credible evidence that he had anything to do with the Titanic tragedy beyond coincidence (his not taking the voyage).

The Curse of the Mummy: Among the most bizarre legends is the tale that a cursed Egyptian mummy on board brought about Titanic’s doom. This modern myth stems from British editor William T. Stead, who himself sailed on Titanic and perished in the sinking. In the years before, Stead had been playfully spreading spooky stories about a so-called “Unlucky Mummy” in the British Museum. After the disaster, a surviving passenger recounted Stead’s mummy tale to newspapers, and within a month The Washington Post ran the headline: “Ghost of the Titanic: Vengeance of Hoodoo Mummy”. Different versions of the story claim that the mummy (an artifact from the 13th century BC, nicknamed the “Unlucky Mummy”) was either in the luggage of a passenger (Molly Brown) or had been sold by the British Museum to an American and was being shipped on Titanic. The truth is far less thrilling: the supposedly culpable mummy artifact is still in the British Museum in London to this day and was never on board Titanic. This “curse” is firmly in the realm of urban legend – no curse sank Titanic, but rather a very real iceberg did.

Latest Developments up to 2025

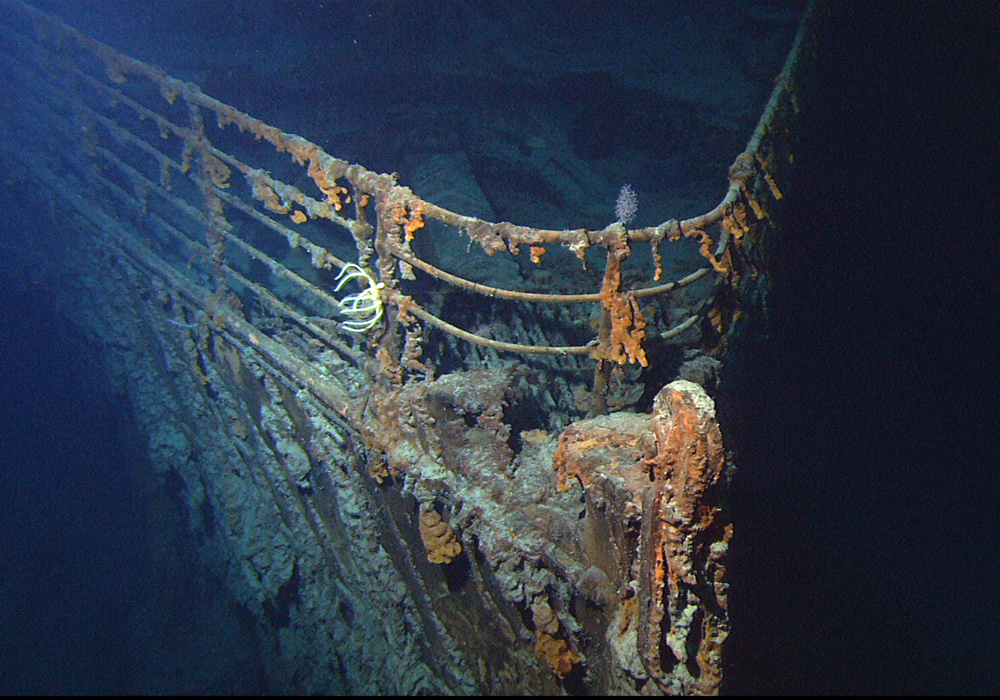

Discovery of the Wreck: For decades after the sinking, the Titanic lay lost on the ocean floor until it was finally located in September 1985 by a team led by Dr. Robert Ballard. The wreck is situated at a depth of about 3,800 meters (nearly 2.5 miles) on the floor of the North Atlantic, roughly 650 km southeast of Newfoundland. Upon discovery, it became clear the ship had not sunk in one piece – it lies in two main sections about 600 m apart on the seabed. In the years and decades that followed, the wreck was visited numerous times by manned submersibles and robots. Expedition reports confirmed eyewitness accounts of the ship’s breakup and also provided new insights: for example, hull plates were found in the debris field, supporting the idea that rivets and seams had failed (rather than a single long gash). Since 1987, thousands of artifacts – china, luggage, pieces of the ship’s fittings – have been recovered and displayed in museums or traveling exhibitions. However, salvage efforts are controversial – critics consider the wreck a gravesite that should be left undisturbed. A planned attempt to recover the wireless telegraph (Marconi station) in 2020 was blocked by courts and delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic. The U.S. and UK have agreed that any interference with the wreck must meet strict conditions to respect the dignity of the over 1,500 dead. Today the wreck is steadily being consumed by rust-eating bacteria and corrosion – experts estimate that in a few decades large portions of the ship may collapse or disappear.

Modern Expeditions and 3D Scanning: Recent expeditions have focused on digitally capturing and analyzing the entire wreck. In the summer of 2022, Titanic was thoroughly scanned using specialized submersibles and underwater lasers. The UK-based firm Magellan Ltd. compiled a high-resolution 3D model of the wreck from this data. This “digital twin” of Titanic allows one to view the ship as if the water were removed – a first that reveals details difficult to discern by eye during dives. Experts hope the data model will yield new forensic insights into the exact mechanics of the sinking. For instance, in 2023 Titanic analyst Parks Stephenson noted evidence suggesting Titanic may not have simply sideswiped the iceberg, but possibly ran over a submerged ledge of ice. This “grounding” theory was proposed as far back as 1912 and could be corroborated or refuted by the new scans. In addition, the 3D model digitally preserves the wreck’s current state for posterity, as the physical ship continues to deteriorate from bacteria and ocean currents. Accompanying the scan project, documentaries are being produced that will likely provide fresh insights. Famed director James Cameron, who made the Titanic Hollywood film, has also continued to conduct dives and experiments – in 2022/23 he hosted a TV special reexamining open questions (such as the angle of the break-up or survival times in the water) with scientific tests. The enduring fascination with Titanic thus drives ongoing investigations and technical innovations in underwater archaeology.

Tragedy of the 2023 Titan Submersible Mission: Titanic has made headlines even in recent times, as shown by a tragic event in June 2023. A private mini-sub named Titan, which aimed to bring paying tourists to the Titanic wreck, imploded during a dive. All five people on board were killed. The Titan tragedy underscored the extreme risks involved in deep-sea dives to the wreck. At the same time, it thrust Titanic back into the public spotlight – even reinvigorating some old myths and misinformation on social media. The international search for the missing submersible captured global attention, once again feeding the fascination with Titanic. In the aftermath, news agencies felt compelled to debunk circulating false claims (such as the Olympic switch) yet again. Over a century after her sinking, Titanic remains a subject that intertwines technological adventure, scientific curiosity, and human tragedy. Each new discovery – whether at the physical wreck site or in historical archives – helps to further complete the picture of Titanic’s story and separate truth from legend.

Key Figures of the Titanic

Technical Data and Capacity: The tables below summarize key technical specifications of the RMS Titanic, as well as information on passenger complement and rescue capacity.

Technical Specifications of RMS Titanic

| Shipyard | Harland & Wolff (Belfast, Northern Ireland) |

| Operator | White Star Line (IMM Group) |

| Ship Type | Olympic-class ocean liner |

| Launch Date | May 31, 1911 |

| Maiden Voyage | April 10, 1912 |

| Length | 269.1 m |

| Beam (Width) | 28.2 m |

| Height | 53.3 m |

| Tonnage | 46,329 GRT |

| Propulsion | 3 propellers, steam engines, turbine |

| Power | Approx. 46,000 HP (34 MW) |

| Speed | Max. approx. 23 knots |

| Decks | 9 (labeled A–G) |

| Funnels | 4 (3 functional, 1 dummy) |

| Passenger Capacity | 2,435 passengers |

| Crew | Approx. 892 |

| Lifeboats | 20 boats for 1,178 people |

Passenger Load & Disaster Statistics (1912)

| Total People on Board | Approx. 2,224 |

| Survivors | 706 people |

| Fatalities | Approx. 1,500 |

| 1st Class Survival Rate | ~62% (Women: 97%, Men: 32%) |

| 3rd Class Survival Rate | ~25% (174 of ~710) |

| Water Temperature | -2 °C |

| Time Until Sinking | 2 hrs 40 min (11:40 PM – 2:20 AM) |

| Wreck Location | 41°43′ N, 49°56′ W (approx. 650 km SE of Newfoundland) |

📚 Quellen / Sources:

• Encyclopedia Britannica – Titanic

• History.com – Titanic Overview

• National Geographic – Titanic Features

• U.S. National Archives – Titanic Records

• NOAA – Titanic Fact Sheet

• BBC – Titan Submarine Incident (2023)

• Magellan Ltd – Titanic 3D Survey

• Netflix / NatGeo – «Titanic: 25 Years Later with James Cameron» (2023)

• Wikipedia – Sinking of the Titanic

• Titanic Inquiry Project – Original Hearings & Testimonies